From Lynching to Lunching

or how we live with terror

Last month I went on a civil rights pilgrimage to Selma and Montgomery Alabama with 26 people from my church + a friend from Boston who had led such pilgrimages many times before.

At the base of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, day 2.

It took us 5 years from the time we first started talking about going, to actually go. Which shows you how much patience I have learned in my current gig!

Among the things that stalled us along the way were two big questions:

how to do this kind of a trip in a majority white/but significantly multiracial church?

And how to do it in a way that would allow everyone to go, regardless of ability to pay?

The second question was actually not that hard to solve: raise enough money to scholarship everyone who needed it.

The first question proved a lot trickier. The primary destination of the pilgrimage, EJI’s Legacy Museum, immersively traces the legacy of racial terror in America from the Middle Passage (12 million African people transported across the ocean, where 2 million of them met their deaths enroute) through to mass incarcerationn–and connects all the dots in between to reveal a portrait of the systemic enslavement and torture of an enormous number of human beings.

Let’s just say: the museum (as well as everything else we witnessed) promised to be a very different experience for the Black members of my church than for the white members. How could I pastor them both in the moment?

To drill in to the naked truth: how could I make sure my white members didn’t say anything ignorant or accidentally hurtful to Black members? Or unconsciously expect the Black members to provide emotional support them when their encounter with this history (and present-day systems!) wrecked them? Or inevitably have 18 different epiphanies on the pilgrimage then ask the Black members of our church for absolution to relieve their discomfort at the benefits of whiteness?

And how would the Black members of my church resist the pressure to become teachers or priests offering that absolution, and metabolize their own grief and trauma in real time with a whole audience of their white coreligionists? You can see why, eager as I was to go, I kept kicking the can down the road.

Then God provided the kairos moment and the Holy Spirit leadership. Brittany, one of my awesome church members who is a social worker in child welfare and a total badass, offered to prepare and lead us. A Black woman, she had just finished a DIY pilgrimage and felt she was emotionally capable of being in a dual role. I would handle the logistics, she would do 6 sessions of compulsory antiracism training to get us emotionally and spiritually ready for this encounter, and my friend June would meet us in Alabama as extra support for the whole group: teaching, guiding, comforting, calling in. We’d stay in Airbnbs rather than hotels so we would have to really deal with each other: overflowing toilets, family-style dinners, bedhead, moods. All of us giving up some measure of comfort and privacy and predictability to take a giant step deeper into Beloved Community.

Brittany’s giant beautiful energy reviving us after the Legacy Museum.

TL:DR–it was an incredible trip. Putting the work (and prayer!) in ahead of time paid off. People were READY. They were their best selves in community. They were careful with each other, empathetic, assuming the best of one other. White folks took correction graciously and humbly. As a whole, we experienced a range of deep feelings–including joy and silliness–but weren’t fragile or reactionary or defensive.

I was a tiny bit worried I’d be so much in Leader Mode that I’d dissociate from my own feelings during the experience, skating on the surface. And certainly, dealing with airport transferes and plumbers and grocery shopping for 28 people in 3 different homes, I had to bracket my feelings and, a la Debra Winger in Broadcast News, make time to cry. I’d go for a bad jog by myself, and cry when I saw the train tracks that blocked city-dwellers from quiet enjoyment of the Alabama River, tracks laid by enslaved people for the express purpose of bringing more enslaved people to the auctions more efficiently. I cried when I saw how depressed Montgomery was, a caricature of urban blight and neglect of places white people have abandoned, knowing that the city has only in the past few years finally elected their first Black mayor (and he’s UCC!).

Near the Alabama River and the train tracks.

There are signs that Bryan Stevenson’s vision is translating into an economic boon for the area as new hotels and restaurants are coming online–but for now, the downtown area is oddly piebald, empty lots and bedraggled abandoned stores beside gorgeous murals and hip restaurants and the looming alabaster gaze of the state capitol.

Crosswalk painted with a representation of the Selma to Montgomery March footsoldiers’ feet, in front of the state capitol.

I tried to stay with feelings and not let them crystallize into judgments, as Brittany had urged us. My enneagram coach, the wise and badass Micky ScottBey Jones, has been teaching me that as an enneagram 3 I find feelings inconvenient and at odds to working through my to do list–so I need to actually put feelings ON my to do list.

Then biggest cry came unexpectedly, and publicly, despite my desire to keep my feelings to myself so I didn’t make it about me.

The morning started clear and bright. The group was bonding and spirits were high. We gathered to sing and pray out front before entering. This song, Lead With Love by Melanie DeMore, had become a favorite: eminently singable and on point.

We talked over logistics for the day before crossing the threshold and leaving time and space behind. I thought 2 hours in the museum would be plenty. Brittany said we needed at least 3. Ever mindful of accommodating different ages and abilities, feelings and moods, I suggested that people could take breaks when they needed, even walk back to the main house a couple of blocks away for a snack.

But Brittany wisely overruled me, saying: “the people who lived though the events you are about to bear witness to couldn’t get away, not for their whole lives. I am going to ask you to stay in it, for 3 hours. To allow yourself to be uncomfortable, knowing you can go back to your lives by lunchtime.”

I entered the museum a little behind everybody else, and so I was alone when I walked into the first room, which was floor-to-ceiling video screens of giant rolling waves on the open ocean, a simulation of the Middle Passage. I could have stayed in that room forever, just marinating in the grief of it, honoring 2 million humans who found watery graves before the slave ships landed on the other coast, setting in motion generation upon generation of torment, loss and pain.

I took care to read and experience everything along the way. The museum is so well done that even when it ignites intense pain, it is not ponderous. Before I knew it, it was almost 1pm, and I was only a little more than halfway through before I had to hustle over to the onsite cafe to pay for the group’s lunch.

I was at the exhibit devoted to lynching, the white terrorist tool to hammer newly liberated, post-Reconstruction Black Americans back into a position of submissiveness, political disenfranchisment and economic subservience. Lynchings were most likely to happen on election days–not a coincidence. The faces of dignified Black men sitting for their portraits as mayors, US congressmen and ambassadors appeared–and then disappeared, in one short wave.

What took their place for the next 60 years was the portraiture of wrecked bodies from throughout the South, but also in Oregon, California, and dozens of other states stained by white violence and hatred, evil desire and greed. Orchard after orchard of strange fruit, blood on the leaves and blood at the root. Museum historians had painstakingly gathered up the stories of each lynching: names, dates, locations, newspaper clippings and commemorative postcards. Soil was taken from each location and put into clear glass ball jars, marked with the county name, a terrifying terroir.

But it was 1 o’clock, time to put away feelings, to move from lynching to lunching. I made it to the café, and we counted off. I found my way to the back of the line where I talked with several of my mothering church ladies about what we had experienced. And that’s when I lost it. Ugly crying. “I just don’t understand how we can do that to each other,” I choked out between sobs, as they leaned in and held me.

Although I do actually understand how. And I am not immune, except by degree. We humans are taught very young to scapegoat. To project our sins onto an unlucky Other, then dissociate from what we have done, or what has been done in our names/or for our benefit even if we are not the ones holding the rope, the cross, the torch.

I just finished reading Barbara Kingsolver’s stunning Demon Copperhead, a gloss on David Copperfield’s harrowing story of child abuse and neglect, this time set in modern-day Appalachia against the backdrop of the opioid epidemic. One of Kingsolver’s Black characters says, “Certain pitiful souls around here see whiteness as their last asset that hasn’t been totaled or repossessed.” Looking down on others is a quick fix to feeling better about ourselves. That impulse, assigning caste and taking it to a violent extreme, produces genocide, fast and slow.

Given how entrenched all of this racial trauma and terror is in our society, what can we possibly do to root it out, forever?

One of the simplest and best things Bryan Stevenson asks us to do (and if you haven’t watched his TED talk or seen the movie based on his book Just Mercy or this short talk about representing a young boy who was in adult jail awaiting trial please stop everything and go do it right now) is: GET CLOSE.

Get close to the pain and the suffering. “Engage and invest and position ourselves in places where there is despair,” Bryan says. Visit incarcerated people, food banks, encampments. And don’t swoop in as a savior, pitying, a different kind of condescension but still destructive. Go in expecting to meet Jesus rather than be Jesus, as Matthew 25 hints.

But the “getting close” doesn’t just pertain to prisons and poverty and skin tone. Whoever you are, however you identify, whatever privilege you enjoy–go and find someone who is different, and GET CLOSE. If you’re rich, make poor friends. If you’re cis, make trans friends. Think of all the ways we caste each other, and break caste.

The power of that proximity will change things–most of all you. And you might get to be part of bringing more justice to the world. And justice, Bryan says, is good for everybody.

Brittany asked us as we prepared for this journey, “If you’ve never learned this history, what has allowed you to stay ignorant of it?” And her voice echoes in my ears, “If you can turn away from this history and this present day reality–don’t. Choose to stay with it. To bear witness.”

I feel some of you recoiling from here. Isn’t the world already too much for many of us without us intentionally getting closer to suffering, and the sufferers? I don’t think our psyches were really meant to absorb so much horror from so many places, as media and social media and jet travel have allowed us to.

But here we are. The more privilege we have to ignore it, the more obligation we have to face it. Being deliberate and intentional about HOW we will face it helps. So does doing something–praying and singing with others, making a plan of collective action–so we don’t feel helpless and hopeless, so our feelings have somewhere to go.

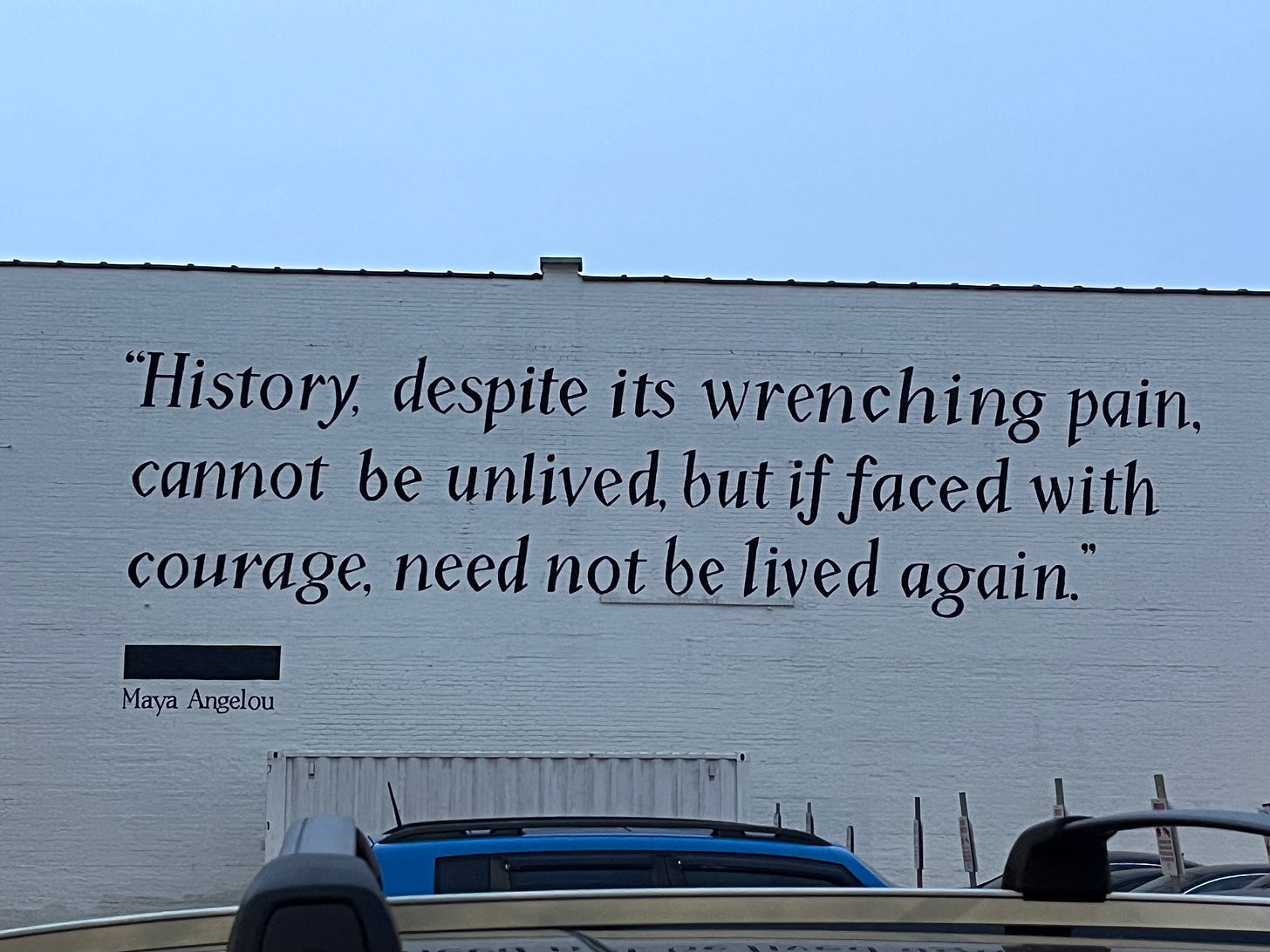

Street art in Montgomery.

The thing about getting close is: it allows us to really see in detail. Getting close is the antidote to feeling helpless and hopeless, because what we see goes from a mass of horrifying stories about a mass of hurting people, to something specific, local, real–the right size for a human psyche. The right size to awaken curiosity, love, energy.

Our pilgrimage group held a learning hour when we came back from Alabama (which you can see here if you’re curious, passcode .YGJz9tC).

I was, frankly, stunned at the congregation’s response. My church folks, good Berkeley social justice warriors, are interested in a LOT of issues but we don’t often find ourselves all moving in the same direction at the same time. But we had a full house at the learning hour. People stayed well past 1 o’clock brainstorming how we would carry this work forward, understanding that the pilgrims were a part for the whole, but that the work of racial justice is up to all of us. Two ideas among many floated to the top:

A few years back we were instrumental in starting the Black Wealth Builders’ Fund with other UCC churches. It’s a zero percent interest loan fund to help Black families build wealth through home ownership, and the loan is only paid back when the home is refinanced or sold. We talked about recommitting to this cause for the long haul.

And because the call is not just to raise money (or read a book! White people, move beyond the Racial-Justice-Book-Club to some real action! I beg you. Sorry if that’s rude!), there was broad interest in getting involved with supporting people as they leave incarceration: to help them find a strong start as they begin life again. If you’re in the Bay Area and want to work with us, one really great organization we work with is Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity, which works on prison policy and decarceration strategy. They also happen to be hosting a 22-mile walk from Berkeley to Alameda this Saturday, to literally walk the equivalent of the length of Gaza, in solidarity with those who suffer there.

Ok. I’ve been laboring over this post for weeks and it’s time to write ~10 million things for Holy Week, so I’m going to hit send. But I want to leave you with this one last image. As I raced from the lynching exhibit out to the cafeteria, I was stopped in my tracks in the gallery of African American art. Specifically, by a Kehinde Wiley portrait that I couldn’t turn up on the internet, so here’s a stand-in below.

Kehinde Wiley (who famously was the first Black artist to paint presidential portraits, for the Obamas) has a unique and resonant style. It harkens back to oil portraits of the ruling class from bygone centuries, but always with Black subjects framed in a riot of flowers, fruits, and excess of luxe joy. A hint at what sometimes is, and may yet be enduringly. How brilliant to end a museum so steeped in sorrow and truth with the beauty born of Black imagination.

Thank you, Bryan–and all who work with him at EJI.

gratitude for the comprehensive thought commitment and resources given to

this pilgrimage. Thank you for sharing all

the complexity in a meaningful resonant way!!

I, and my white Congregational Church teenage brothers and sisters held countless civil rights rallies and sung untold choruses of "We Shall Overcome" in the early and mid-60's while we barley dipped our toes into civil disobedience. We were well intended; we were oh so mildly disruptive and; we could occasionally find some glimmer or success. In college in the late 60's and as a married student, we lived in a small Tennessee town where the basement of the county courthouse served as the meeting place for the KKK. On the day Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated many in the community celebrated. What had been modest embers of civil rights interest as a young teen were now stoked into a burning desire to do more -- get involved -- take a place in trying to be a solution rather than a problem. Fairly early in my professional career I was given a unique opportunity to work with a minority business neighborhood in Atlanta, GA to build a more solid economic foundation for that community. Serving on the City Council, at that time, was John Lewis and the Mayor was Andy Young. Martin Luther King III was an up-and-coming young politician; H. Rap Brown was leading a Muslim enterprise in our business district; Hosea Williams was, at the time, a political gadfly who moved mountains by his dogged agitation; Ralph David Abernathy's church was across from my office. John Lewis became a good personal friend and, as with every cause he ever entertained, he worked tirelessly with me to improve economic conditions. He touched me in ways I can't describe. A year after his passing I took my teenage grandson to the Edmund Pettus Bridge and stand on the spot where John was so brutally beaten. I am ashamed to admit I just couldn't find the words to share with him at that moment -- and I couldn't explain how little had truly changed from my teenage version of We Shall Overcome to his teenage life today. All I could do was cry and hope he understood.